On a narrow lot in Pasadena, a local couple stands amid overgrown grass imagining a cluster of cottages that could soon rise where a single aging duplex once stood. For years, they were warned that turning this parcel into a small housing development would mean endless city council meetings, months of paperwork, and hefty fees. But in early 2025, their architect delivered surprising news: a new California law called SB 684 could let them split the lot and build up to 10 homes with ministerial approval – no public hearings – and get permits in as little as 60 days. In a state notorious for red tape, this felt like a seismic shift. “It’s like the process went from molasses to lightning,” the architect laughs, noting that SB 684 is part of a broader movement to streamline small housing development permits and spur more homes.

Such scenes are playing out across Southern California. In Los Angeles, an aspiring small-scale developer eyes an empty R-3 zoned lot sandwiched between apartment buildings, now envisioning “starter homes” instead of a prolonged battle at City Hall. In Long Beach, a property owner with a large backyard thinks about carving out a few townhome lots for her children. And in Pasadena, planners are fielding calls about this little-known law that promises a lot – literally – in a short time frame . SB 684, a 2025 multifamily housing law in California, is turning the once Sisyphean task of building small infill housing into a more straightforward affair.

What Is SB 684? Legislative Background of the 2025 “Starter Homes” Law

SB 684 (authored by Senator Anna Caballero) is a California housing law signed in late 2023 and effective July 1, 2024 . In a nutshell, SB 684 requires cities and counties to ministerially approve small housing subdivisions of up to 10 units, on qualifying urban infill sites, within a 60-day review period . “Ministerial” approval means the project is checked against objective standards (like building codes and zoning rules) but no discretionary review or public hearing is required . If the project meets the preset criteria, the city must say yes – and fast. If officials drag their feet beyond 60 days, the application is deemed approved by default .

This law builds on the earlier Starter Home Revitalization Act of 2021 (Assembly Bill 803) , which aimed to make it easier to create “small home lot” developments. SB 684 expands that idea dramatically . As one legal analysis noted, SB 684 “provides for streamlined, ministerial processing of certain residential projects in multifamily zoning districts consisting of no more than 10 single-family homes,” facilitating the construction of smaller, more naturally affordable “starter” homes . In other words, the state legislature recognized that missing-middle housing – duplexes, fourplexes, bungalow courts, cottage clusters – are often tied up in the same bureaucracy as 50-unit apartment buildings, and they wanted a fix. By targeting projects 10 units and under, SB 684 carves out a niche of small-scale development and puts it on a fast track.

Governor Newsom’s signing of SB 684 came as part of a broad housing package aimed at tackling California’s housing crisis . Over 60 housing-related bills were signed in 2023, all geared toward accelerating housing production and removing barriers at the local level . SB 684’s particular focus is to unlock “starter” home development in existing neighborhoods – think of 6, 8 or 10 modest homes where maybe one old house stood before – without the usual gauntlet of delays. This aligns with California’s recent moves like SB 9 (2021), which allowed duplexes and lot splits in single-family zones, and AB 2011 (2022), which opened commercial lands to housing by-right. The message from Sacramento is clear: small projects shouldn’t face big hurdles.

A 60-Day Approval? Why SB 684 Is a Game Changer for Permit Timelines

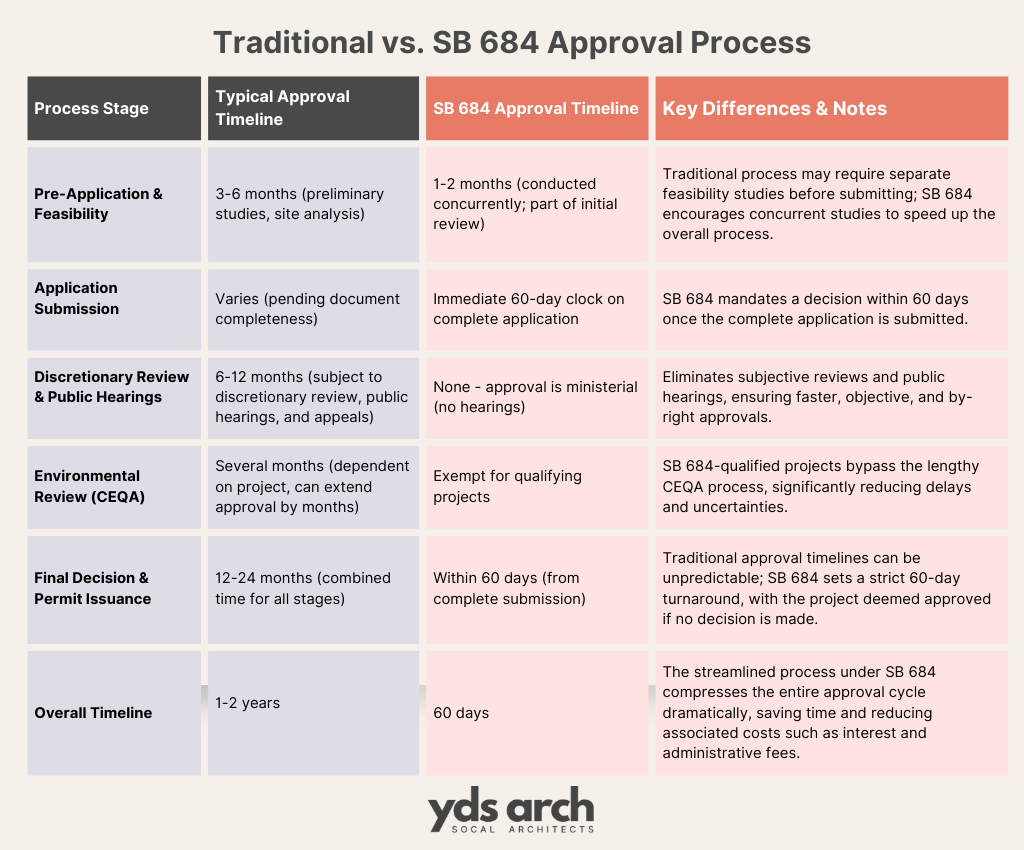

To appreciate SB 684, one must understand how traditional permitting timelines have frustrated builders of even the tiniest subdivisions. In many California cities, getting approval for a 4-unit condo project or a 6-lot subdivision could take months or even years. Public hearings, environmental reviews, design review boards, and potential NIMBY appeals all add layers of time. For instance, in San Francisco the median time to approve a multifamily housing project was 34 months (nearly three years) between 2018 and 2021 . Los Angeles is hardly faster – one study found that for similar mid-size projects, those undergoing discretionary review had a median approval time of 748 days (over 2 years), whereas by-right projects (with no hearings) took under 500 days . In short, discretion = delay.

SB 684 torpedoes this problem by imposing a strict 60-day shot clock on approvals . This timeline, mandated by the state, forces local agencies to do what was previously unheard of for subdivisions: make a decision in two months. If the city doesn’t act, the project is automatically approved by law . For comparison, California’s Permit Streamlining Act typically gives local governments 120 days after an application is complete to approve many housing projects – and cities often paused or deemed applications incomplete to stall the clock. SB 684 explicitly requires a yes-or-no within 60 days from the day of submission of a complete application, with no extensions to accommodate hearings or studies .

Equally important, SB 684 bypasses the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) for qualifying projects. Environmental review can add many months (or even years if lawsuits occur) to a project. Under SB 684, eligible 10-unit-and-under infill developments are statutorily exempt from CEQA’s requirements . This means no environmental impact report, no lengthy assessments – as long as the site meets the law’s criteria (which intentionally exclude sensitive lands, as discussed below). By eliminating CEQA review and public appeals , SB 684 removes two of the biggest sources of delay and uncertainty.

The resulting timeline compression is dramatic. What might have been a 12- to 24-month entitlement slog can shrink to just 8 weeks for approval. Even building permits are sped up: SB 684 actually allows builders to obtain a building permit at the tentative map stage, before the final subdivision map is recorded . This is huge – it lets construction commence while the final mapping paperwork catches up. The law permits cities to issue these early building permits as long as the developer provides necessary guarantees (like bond insurance or agreements to finish the subdivision process) . In practice, this could shave additional months off the project timeline, because developers won’t be stuck waiting for the final map to start grading and laying foundations.

To be sure, a 60-day turnaround isn’t entirely unprecedented – California mandated a similar timeframe for ADU (Accessory Dwelling Unit) approvals a few years ago. Many planning departments struggled to meet the 60-day ADU permit rule that took effect in 2020 , but gradually, processes adapted. SB 684 extends the same urgency to small multifamily projects. Cities like San Diego have already created a one-stop ministerial process for SB 684 tentative maps; in San Diego’s case, an SB 684 subdivision is processed as a simple “Process One” administrative action, with no public notice or hearing and a binding decision within 60 days . The expectation is that other cities in Southern California – Los Angeles, Pasadena, Long Beach, and others – will similarly handle SB 684 projects through expedited internal review. Pasadena’s planning department, for example, has acknowledged that decisions must be made “within 60 days, without holding public hearings or discretionary reviews” under SB 684 , and Los Angeles officials are updating their workflows to comply with the state mandate.

For small-scale developers, this time savings directly translates to cost savings. Fewer months paying interest on land loans, fewer consultant fees for prolonged processing, and less risk of market conditions changing mid-approval. It also means increased certainty – if you meet the rules, you can count on a green light by Day 60. This level of predictability is a boon to “mom and pop” builders who don’t have the resources to endure multi-year entitlement battles.

Eligibility Criteria: What Kinds of Projects Qualify Under SB 684?

Before one gets too excited about fast approvals, it’s crucial to understand which projects are eligible for SB 684’s streamlining. The law is tailored to urban infill, small-scale subdivisions. Here are the key eligibility criteria that a project must meet to take advantage of SB 684’s provisions :

- Zoning and Location: The property must be zoned for multifamily residential development (e.g., R-2, R-3, R-4, or similar zones that allow multiple dwellings) . Initially, SB 684 does not apply to single-family-zoned lots unless they are rezoned or (starting mid-2025) made eligible by a companion law SB 1123. The lot must also be in an urbanized area – specifically within an incorporated city or an urban cluster – and be substantially surrounded by urban uses (so you can’t use SB 684 to drop a 10-pack of homes in the middle of farmland or wilderness) .

- Lot Size: The existing parcel to be subdivided must be no larger than 5 acres . This ensures SB 684 is used for relatively small infill sites, not large greenfield tracts. In practice, 5 acres is quite generous (imagine roughly a 5-acre block within a city). Many SB 684 projects will likely be on much smaller lots – even a standard suburban lot (say 7,500 sq ft) could potentially be split into several small lots under this law, as long as other criteria are met.

- Maximum Units and Parcels: The subdivision can result in 10 or fewer new parcels, and the housing development project built on those parcels can have 10 or fewer residential units total . In most cases, this means you’re dividing one lot into up to 10 lots and putting one single-family home on each (for 10 units total). However, SB 684 could also be used to create a couple of lots each with a duplex or triplex, as long as the total unit count is ≤10. It offers flexibility: you could map 5 lots and plan 2 units on each, for example. The key is the project’s overall unit count stays at 10 or below.

- Minimum Lot Size: Each of the newly created lots must be at least 600 square feet in area . This is a very small lot (think micro-townhouse or cottage lot) – by design, the law doesn’t want cities to block a project just because the new parcels would be smaller than the usual local minimum (which often is far larger). SB 684 explicitly overrides local minimum lot size, width, and depth requirements, except for that 600 sf floor . This opens the door to creative tiny lots (perhaps for attached townhomes or bungalow court cottages).

- Adequate Infrastructure: The site must be served by public water and sewer systems . This is to ensure that these infill projects occur where city services already exist (typical of urbanized areas) and avoid issues of wells or septic systems.

- Unit Size Cap: The average floor area of the new homes cannot exceed 1,750 square feet . This means if you build 10 houses, their total habitable square footage combined must average 1,750 or less – effectively discouraging McMansions. SB 684 is about modest homes; capping unit size encourages affordability by design (smaller homes tend to cost less and sell/rent for less). For context, 1,750 sq. ft. is around a three-bedroom townhouse size. A project could have some units larger and some smaller as long as the average stays under the cap.

- Meet Density Expectations: If the parcel is listed in the city’s Housing Element site inventory (a roster of sites the city identified for housing), the project must deliver at least the number of units the Housing Element projected for that site . If not listed, then the project must use at least the maximum allowable density of the zone (or at least 66% of it, per updates in SB 1123 ). This prevents under-building – for example, if zoning allows 10 units, you can’t just build one giant house and still claim SB 684; you need to maximize the housing potential (which fits the law’s goal of more homes).

- No Prior Lot Split under SB 9 or SB 684: The property cannot have been previously subdivided using SB 9 (the two-lot split law) or SB 684 . This prevents serial splitting that could otherwise exceed the unit cap. In essence, each lot gets one bite at the apple – you can’t chop a lot into 2 with SB 9 and then try to chop those into more with SB 684, or vice versa.

- No Demolition of Affordable/Recently Occupied Units: The project cannot require demolishing or altering certain types of housing that California law protects . This includes housing with rent control or affordability covenants, housing occupied by tenants in the past 3 years, or units withdrawn from the rental market under the Ellis Act in the past 15 years . In short, SB 684 is for new housing on underutilized land, not for displacing existing residents or affordable units. If the site has had tenants or affordable housing recently, it’s off-limits for this fast-track process.

- Avoid Hazardous and Environmental Zones: Certain lands are excluded for safety and environmental reasons. The site cannot be in a very high fire hazard severity zone, on a hazardous waste site, in an earthquake fault zone (unless building to code for that), on prime farmland, in wetlands, in protected habitat areas, or in a floodway . Essentially, SB 684 is meant for typical urban infill lots – not for building in disaster-prone or ecologically sensitive locales.

- Ownership and Affordability: The new housing can be any form of ownership: fee simple lots, condos (common interest developments), co-ops, or community land trusts . A homeowners’ association cannot be required by the city unless one is normally mandated by state law for that type of project . Also, any local inclusionary housing ordinance (requiring a percentage of affordable units) still applies – SB 684 doesn’t exempt projects from contributing to affordable housing if the city has such a rule, so a developer might need to offer one of the 10 units at a below-market price if required. Notably, an extension law (SB 1123, effective mid-2025) even allows tenancy-in-common arrangements to qualify , ensuring alternative paths to homeownership are possible under SB 684’s umbrella .

In summary, an ideal SB 684 project scenario would be: an infill lot in L.A. or Orange County, zoned R-3, around say 15,000 square feet in size, currently maybe an old vacant structure or underused space, where a builder can map out, for example, 6 small lots and build 6 detached townhomes, each 1,500 sq. ft., with one of them designated as an affordable unit if required locally. The lot is surrounded by other houses and apartments (so urban), has utilities, and no one is displaced. This would sail through under SB 684. But if that same lot had a rent-controlled fourplex occupied last year, the developer would not be able to use SB 684 to tear it down and replace it – the law guards against that outcome.

Benefits for Small-Scale Developers: Faster Approvals, Less Red Tape, More Certainty

For small-scale developers, architects, and homeowners-turned-builders, SB 684 offers a suite of benefits that can make previously infeasible projects pencil out:

- Speed and Predictability: The 60-day approval timeline gives a clear horizon. Traditional processes could drag on unpredictably; by contrast, SB 684 guarantees that in about two months you’ll have an answer (and likely a yes if you met the criteria). This speed reduces carrying costs on loans and taxes, and allows faster sales or occupancy of the new homes, improving the project’s financial viability.

- Lower Soft Costs: Because SB 684 skips hearings and environmental reports, developers save on costs for planning consultants, attorneys, environmental consultants, and the expenses of multiple plan revisions to appease commissions or neighbor opposition. There’s no need for expensive traffic studies or months of environmental consulting – qualifying projects are exempt from CEQA and discretionary approval by law . Fewer studies and meetings = lower upfront expenditures.

- Reduced Risk of NIMBY Opposition: By removing public hearings and the right to appeal decisions , SB 684 insulates small projects from being derailed by local opposition. Neighbors won’t get a formal forum to object (as long as the project follows the rules). This is a huge relief to small developers who often face vocal resistance even for a handful of homes. With SB 684, if you follow objective standards, community opposition cannot easily stop the project.

- No Quid-Pro-Quo Exactions: In discretionary processes, developers sometimes must negotiate community benefits or face unpredictable conditions imposed by officials. Under SB 684, the city can only apply objective standards (like standard zoning rules for height, design, etc.) and cannot impose unique conditions just because you used SB 684 . The law explicitly forbids standards that would make the project infeasible at the allowed densities, or any requirements solely due to using SB 684 (no “special” fees or arbitrary conditions) . Also prohibited are things like mandating enclosed parking garages, excessive setbacks between units, or low floor-area-ratios that would limit building size . Cities can’t, for example, suddenly require a 30-foot spacing between homes or two covered parking spots per unit; SB 684 demands they stick to reasonable norms (indeed, it references the SB 9 standards – e.g., max 4-foot side/rear setbacks, at most 1 parking space per unit if not near transit – as the guideline for acceptable requirements) . All of this means a more straightforward, transparent process with less arbitrary red tape.

- Empowerment of Small Developers: Large developers often have the capital to endure long entitlements or build 100-unit complexes, but smaller players (maybe a family investor or small partnership) focus on projects under 10 units. SB 684 is almost custom-made for these “small infill” developers. It lowers the barrier to entry, potentially allowing more local builders to participate in addressing the housing shortage. This could diversify who is building housing – not just big corporations, but also local architects, Habitat for Humanity chapters, and “missing middle” specialists. (In fact, Habitat for Humanity supported SB 684, seeing it as a way to “split a single parcel into multiple, smaller properties, each with their own home,” thereby expanding affordable homeownership opportunities .)

- Encourages Affordable Starter Homes: By capping unit size and streamlining the process, SB 684 inherently promotes smaller, likely more affordable units. These new homes are market-rate but modest – often called naturally affordable or “attainable” housing. They are the kind of entry-level condos, townhomes, or courtyard bungalows that California has built too few of in recent decades. For communities, this means more housing options without large, out-of-scale developments, fitting into neighborhood contexts. For developers, it means there’s likely strong demand for these smaller homes, whether for sale or rent, given the shortage of such housing.

In short, SB 684 strips away many of the bureaucratic uncertainties that typically plague small developments. An architect who specializes in such projects notes that it “levels the playing field” – a 8-unit infill project can now avoid much of the red tape that used to make anything under 50 units hardly worth the effort. The faster timeline and streamlined rules may also make financing easier to obtain, since lenders see lower entitlement risk. All these benefits coalesce into one overarching advantage: more small housing projects will actually get built.

How to Take Advantage of SB 684: A Practical Guide for Developers and Homeowners

If you’re a property owner or developer eyeing SB 684 for your project, how should you proceed? Here’s a step-by-step guide to leveraging this new lot split streamlining law in California:

- Evaluate Your Site Eligibility: First, confirm that your property meets the SB 684 criteria. Is it in a multifamily zoning district within a city or urban area? Is it ≤5 acres and mostly surrounded by developed urban uses? Check that no protected units or recent tenants are on site, and that it’s not in an excluded zone (fire hazard, floodplain, etc.). If your lot has an existing house, consider whether that house would stay or be demolished – remember you can’t remove certain types of affordable or rent-controlled housing. If in doubt, consult the SB 684 provisions or a planning professional to ensure the lot is eligible. Many cities (like San Diego and Pasadena) have published checklists for SB 684 projects that include these requirements.

- Plan Your Housing Development (Up to 10 Units): Sketch out what you want to build. Will it be detached homes, townhomes, a small condo building, or a couple of fourplexes? You have flexibility as long as the total units ≤ 10. Decide how to subdivide the land – e.g., creating individual lots for each house versus a condo map for units in one structure. Work with an architect or designer to maximize units while respecting the average 1,750 sq ft size limit (for example, ten 1,500 sq ft homes would be compliant). Ensure your plan meets the objective zoning standards like height limits or design rules of the local code. The city can still require the project to follow things like height, landscaping, or design guidelines (if they’re objective), so your design should be code-compliant. Importantly, no unique design review is required, but expect a plan-check for zoning consistency. This is where experienced architects can be invaluable – they’ll know how to meet city standards on paper so the ministerial approval goes smoothly.

- Prepare a Subdivision Map Application: Because SB 684 involves splitting the property, you’ll need to file a tentative parcel map or tract map (depending on the number of lots – typically 4 or fewer lots is a “parcel map,” more might be a “tract map”). SB 684 doesn’t eliminate the map filing; it just guarantees it’s processed ministerially . Hire a licensed land surveyor or civil engineer to draft the tentative map showing new lot lines, easements, etc. Submit this along with your development plan (site plan, unit floor plans/elevations) as one package to the city. Clearly indicate you are seeking approval under SB 684 – some cities may have a special application or checklist. Ensure the application is complete with all required documents and fees, since the 60-day clock starts only when the city deems your application complete . (By law, if they deny it as incomplete, they must tell you what’s missing within that same timeframe .)

- Mind the 60-Day Clock and Engage Proactively: Once submitted, monitor the timeline. The city has 60 days to approve or deny. Often, planning staff might come back with corrections or comments (e.g. “objective standard X not met, please adjust setback” etc.). Under SB 684, if they intend to deny, they must provide a written list of deficiencies and how to remedy them within the 60 days . Be prepared to respond quickly to any feedback – if you can address minor issues within the window, do so. Many SB 684 projects will likely get a “conditional approval” where the city says yes, provided you comply with certain standard conditions (like final map conditions, fees, or slight plan tweaks). Work collaboratively with the plan checkers; remember, they’re on a tight deadline too. It may help to politely remind the planning department of the deemed approved clause – they know if they miss the deadline, you could claim automatic approval, which motivates everyone to stay on schedule.

- Secure Building Permits (Early if Possible): One golden nugget in SB 684 is that you can get building permits even before the final subdivision map is recorded . After your tentative map and project are approved, talk to the city’s building department about pulling permits under the SB 684 provision. You might need to provide a bond or guarantee that you’ll complete the subdivision process and any required public improvements (like utility hookups or street widening if needed) . Start preparing detailed construction plans for plan check while the tentative map is in process, so you’re ready to submit for building permit as soon as you have the tentative map approval letter. In many cases, you could begin construction (site grading, foundation, etc.) while finalizing the map paperwork. This concurrency can cut down the total project timeline significantly – a huge advantage for a small developer trying to deliver homes quickly.

- Consider Professional Guidance: While SB 684 simplifies things, professional guidance is still key. Engaging a planner or architect experienced in California’s new housing laws can smooth out any kinks. For example, YDS Architects, a Southern California firm specializing in small-scale infill housing, has been at the forefront of navigating laws like SB 9 and ADUs to maximize housing on tricky lots. In one Los Angeles project, YDS Architects leveraged SB 9 and ADU provisions to design a 7-unit multifamily compound on a single lot, integrating an existing home, a new 3-story duplex, and a detached 2-story ADU – an innovative approach to add housing within a small footprint . Firms with this kind of expertise can similarly help clients capitalize on SB 684, ensuring designs meet all objective standards and making the ministerial approval nearly a rubber stamp. Don’t hesitate to consult with such experts; they can handle the technical details and coordinate with city staff, letting you focus on the big picture.

- Stay Informed on Updates (e.g., SB 1123): Housing laws evolve. SB 684 is being augmented by SB 1123 (effective July 1, 2025), which will extend the same ministerial subdivision allowance to vacant lots in single-family zones as well . It also tweaks some criteria (e.g., reducing max lot size to 1.5 acres in that context, requiring at least 66% of max density if not a Housing Element site, etc. ). Keep an ear out for these changes, especially if you have projects in single-family areas or if your city refines its processes. Also monitor local ordinances – while cities cannot opt out of SB 684, they might pass local guidelines or fee adjustments for these projects. Being up-to-date will help you seize new opportunities (imagine, by late 2025, being able to use SB 684/SB 1123 on an empty single-family lot to build 6-8 homes by-right – that could be a game changer for many suburban communities as well).

By following these steps, developers large and small can make the most of SB 684. In essence, treat it like a streamlined version of the normal subdivision process: you still do your homework and planning, but once you submit, the process should be smooth and swift. Just as importantly, community stakeholders like architects and affordable housing builders should spread the word – many eligible property owners might not even know that their lot could host a handful of new homes with minimal fuss. Knowledge is key to unlocking the potential of this law.

Local Context: How SB 684 Could Play Out in Los Angeles, Pasadena, and Beyond

Southern California’s cities present a patchwork of opportunities for SB 684 implementation. Los Angeles, with its vast expanse of multifamily zoning (R2, RD, R3, R4, etc.), is prime territory. Small apartment buildings or even single bungalows on oversized lots in these zones could be replaced or supplemented by up to 10 units. For example, in East Hollywood or South Los Angeles, it’s not uncommon to see a lone duplex on a 8,000 sq. ft. lot zoned R3. Under SB 684, a developer could subdivide that lot into perhaps 4 separate parcels and build 4 new houses (or more units in a condo configuration) without a single hearing. Los Angeles city planners are incorporating SB 684 into their development services; while L.A. already had a Small Lot Subdivision Ordinance (allowing fee-simple townhomes in multifamily zones), those required discretionary approval. SB 684 will effectively turn small-lot subdivisions into ministerial actions, superseding any local rules that conflicted. The net effect? We may soon see more projects like modest townhome clusters in L.A. neighborhoods, delivered faster. This complements L.A.’s push for “missing middle” housing and the city’s need to hit ambitious housing targets (the city’s state-mandated goal is over 450,000 new units by 2029).

In Pasadena, a city known for its beautiful single-family neighborhoods and a cautious approach to growth, SB 684 is opening new possibilities particularly in transit-adjacent and multifamily areas. Pasadena’s planning department was still deliberating specifics in late 2024 , but the law applies there as in the rest of California. Imagine Pasadena’s Allen Avenue or Los Robles Avenue, where older cottages sit on big deep lots zoned for multifamily – these could be gently intensified with 6-8 cottage homes via SB 684, in a way that respects neighborhood scale. The Pasadena CityStructure blog (an urban development watch site) noted that as of mid-2024, the city was aware of SB 684’s requirements (5-acre limit, 600 sf lot minimum, <1,750 sf units, etc.) and would be adapting local codes accordingly . They also highlighted that SB 684 (and soon SB 1123) would allow such subdivisions even in vacant single-family zones, expanding infill options citywide . It’s a significant shift for places like Pasadena that historically tightly controlled lot splits.

Long Beach and other Southland cities with plenty of infill lots (Santa Ana, Glendale, Anaheim, etc.) may see a boost in small home developments. Long Beach, for instance, has many R-2N and R-3 lots where currently maybe one house exists; SB 684 could catalyze those owners to build a few more homes. Since Long Beach has a strong drive to add housing near transit corridors (Blue Line stations, etc.), SB 684 can be an attractive tool – by-right approval for 10-unit or smaller projects can encourage local developers to take on those infill sites.

Even San Diego, though outside the LA region, sets a useful example: they promptly issued an implementation bulletin in January 2025 guiding applicants through SB 684’s process . In it, San Diego clarifies the same eligibility points (multi-dwelling zones, 75% surrounded by urban uses, inclusionary housing compliance, etc.) and explicitly states the ministerial path (no hearings, no CEQA, no noticing) . We can expect Los Angeles and other counties to mirror this approach. Some cities might initially be slow to advertise the new process (local officials often quietly adjust rather than actively promote state overrides), but savvy developers and architects are already on it.

One concrete example of the type of infill development SB 684 encourages can be seen in the 7-unit multifamily + ADU project designed by YDS Architects in Los Angeles . While that project utilized SB 9 and accessory dwelling unit laws rather than SB 684 (it was completed before SB 684 took effect), it epitomizes the spirit of maximizing a small urban lot. YDS Architects managed to fit seven homes on one lot by cleverly integrating an existing house, adding a new 3-story duplex, and two detached ADUs, all within a compact site . The result was a hidden density that still blends into the neighborhood – exactly the kind of gentle infill that SB 684 is poised to streamline. Moving forward, a project like that might use SB 684 to simply subdivide and build units directly, instead of relying on the patchwork of SB 9 and ADU rules. The ability to create fee-simple homes (each on its own small lot) under SB 684 could be particularly appealing in places like Los Angeles, where there’s demand for entry-level ownership housing. Firms like YDS, experienced in threading the needle of local codes and state law, are likely already gearing up to employ SB 684 for future projects, guiding clients through the new “fast lane” to build small multifamily housing.

Part of a Broader Shift in California Housing Policy

SB 684 is not an isolated initiative; it’s one piece of California’s multifaceted strategy to address the housing shortage by reforming zoning and permitting at the local level. Over the past few years, the state has enacted laws to encourage everything from backyard granny flats to high-rise affordable housing, often by overriding local restrictions. This trend recognizes that incremental infill – adding a duplex here, four townhomes there – can collectively make a big dent in our housing needs if scaled up across thousands of neighborhoods.

Let’s put SB 684 in context with some other recent reforms:

- SB 9 (2021): Allowed duplexes and urban lot splits in single-family zones statewide. SB 9 made it possible to turn one single-family lot into four units (two on each of two lots) ministerially, but it was limited in scope (only residential R-1 zones, max 4 units). SB 684 takes a similar concept (ministerial approval, small project focus) but applies it to multifamily zones and up to 10 units, effectively addressing the next tier of “missing middle” housing.

- SB 10 (2021): Enabled (but did not require) cities to adopt ordinances allowing up to 10 units per parcel near transit or urban centers, overriding certain voter-enacted restrictions. SB 10 was optional for cities and not widely adopted yet. SB 684, by contrast, is mandatory statewide for eligible projects. Interestingly, both target the “up to 10 units” scale, reflecting a policy sweet spot: dense enough to increase housing, but small enough to fit in neighborhoods.

- SB 35 (2017): Created a streamlined, ministerial approval process for larger housing projects in cities failing to meet housing targets, if developers include affordable units. SB 35’s streamlining has been used for some bigger developments (50+ units) with affordability. SB 684 provides similar streamlining for smaller projects and does not require a certain percentage of below-market units (though local inclusionary policies still apply). Both laws exemplify the state’s push for by-right development when certain conditions are met.

- AB 2011 (2022) & SB 6 (2022): These allow housing on commercial-zoned land (like strip malls or office sites) by-right if affordability and labor standards are met. They tackle unused commercial properties. SB 684 instead focuses on already residentially zoned land that’s underutilized. Together, they attack housing scarcity from different angles – SB 684 makes better use of residential land, AB 2011 opens up new land for residential use.

- Updates in 2024-2025: Laws like SB 450 (Atkins, 2024) fine-tuned SB 9 to hasten its approvals (also imposing a 60-day shot clock for SB 9 projects) , and SB 423 (Wiener, 2023) extended and expanded SB 35. Meanwhile, SB 684’s extension SB 1123 (Caballero, 2024) will, as noted, allow up to 10-unit subdivisions on vacant single-family lots too . This means the vision of SB 684 – quick small subdivisions – will penetrate areas that were previously off-limits due to zoning. It’s a logical next step, aligning with the state’s effort to break the monopoly of single-family zoning and allow more homes in all neighborhoods, not just high-density zones. We are essentially witnessing a convergence of policies that make duplexes legal on single-family lots (SB 9), fourplexes easier in low-density multifamily zones (various local ADU ordinances), and now 6-10 unit projects by-right in multifamily zones (SB 684). The cumulative effect could be significant incremental housing production.

California’s housing policy shifts also emphasize homeownership and equity building at multiple price points. By facilitating “starter homes”, SB 684 dovetails with efforts to create more ownership opportunities for moderate-income families who can’t afford the typical $1 million single-family house. A cluster of townhomes or cottage homes could be sold in the $300k-$700k range (depending on region), providing a foothold for first-time buyers. This resonates with the missions of groups like Habitat for Humanity and local housing nonprofits. It’s telling that Habitat for Humanity California supported SB 684 – they see it as a tool to increase affordable homeownership via smaller homes on infill lots, which is exactly their wheelhouse.

From a big-picture perspective, SB 684’s ministerial approval for multifamily housing up to 10 units is another sign that California is moving away from case-by-case bargaining on housing proposals and toward clear rules that say yes. While large projects will still face scrutiny, the state is carving out spheres where local governments must approve housing objectively and swiftly. This can help depoliticize the process for those smaller projects that often fly under the radar but cumulatively add up. It represents a philosophical shift: treating housing akin to a use-by-right when it meets community plans, rather than a privilege that requires extensive negotiation.

Conclusion: A New Chapter for Small Infill Development – and How to Make It Work

As SB 684 takes effect, the urban landscape in places like Los Angeles, Pasadena, and Long Beach may begin to change in subtle but important ways. Empty or underused lots that might have sat fallow – because developing them was too much hassle for just a handful of units – could spring to life with townhomes, cottage courts, or little condo buildings. The law offers a handshake of sorts: build something modest and compliant, and we the state will ensure local government lets you do it, quickly.

For residents, this could mean more housing options in their own communities – maybe your neighbor’s large lot gets a few new homes, or a blighted property down the street transforms into a neat row of bungalows rather than an abandoned eyesore. There will likely be growing pains: cities must adapt to faster timelines, and some neighbors may be surprised to learn a project didn’t require their input at a hearing. But California’s housing crisis has necessitated bold moves like this. The hope is that by speeding up small developments, SB 684 will chip away at the housing shortfall in a way that big developments alone cannot.

For those in the building and design industry, SB 684 is a call to action. Architects and builders who specialize in infill can proactively identify sites and educate owners about this opportunity. Already, design firms experienced in small-lot housing (such as YDS Architects, which has navigated complex zoning to deliver creative infill solutions) are positioning themselves to help clients capitalize on SB 684’s potential. While this isn’t a sales pitch, it’s clear that having knowledgeable partners will be valuable – someone who can say, “Yes, you can actually build 8 homes here by-right, and here’s how we get it done in 60 days,” is going to be in high demand.

As the couple in Pasadena tours their lot with newfound optimism, one can sense a shift from trepidation to excitement. The housing law SB 684 may not solve California’s housing crisis singlehandedly, but on that Pasadena lot – and on countless others like it – it offers a spark of hope. Small by small, lot by lot, these quicker approvals and added homes represent progress that people can see on their own block. SB 684 is essentially turning “Yes, in my backyard” into state mandate – and if successful, it will help make our communities more vibrant, affordable, and inclusive, one little subdivision at a time.

Potential visuals to accompany this story: photographs or renderings of small infill housing developments (like a courtyard of cottages or a row of townhomes) that exemplify what SB 684 projects might look like; a city map highlighting parcels that could benefit from SB 684; and a before-and-after graphic of a lot pre- and post-subdivision. These visuals would help readers grasp the physical scale and impact of SB 684-facilitated projects, complementing the detailed policy explanation.

Sources:

- Allen Matkins Legal Alert on SB 684: “SB 684 provides for ministerial approval of projects with 10 or fewer parcels and housing developments with 10 or fewer residential units” ; “A local agency is afforded only 60 days to approve or deny the project… If it makes no decision… the project is deemed approved.”

- California Senate Bill 684 – Bill Text Summary: Local agency must ministerially consider a subdivision of 10 or fewer parcels and a housing project of 10 or fewer units on a lot zoned multifamily ≤5 acres, substantially surrounded by urban uses… and must approve or deny within 60 days or it’s deemed approved.

- City of San Diego Information Bulletin 414 (SB 684 Tentative Maps): Eligibility includes multifamily zoning, parcel ≤5 acres, 75% perimeter adjacent to urban development, up to 10 parcels/units, min 600 sf lots, units average ≤1,750 sf, comply with inclusionary housing, no demolishing protected units, not in fire hazard zones, etc. Process is ministerial (Process One), no hearing, no CEQA, decision in 60 days.

- YDS Architects – 7-Unit Multifamily + ADU through SB 9 project: “Utilizing a two-unit development under SB 9, the design integrates an existing home with a new 3-story primary dwelling and a detached 2-story ADU… YDS Architects leveraged… SB 9 to maximize density on this urban lot… resulting in a 7-unit multifamily complex, complete with detached ADUs.”

- California YIMBY – By-Right vs Discretionary Approval Timelines: “The median approval time for non-TOC discretionary projects was 748 days, whereas by-right non-TOC projects took less than 500 [days].”

- KQED/SF Chronicle – Slow Approval Data: San Francisco’s median time to approve multifamily housing was 34 months (2018–2021) , underscoring typical lengthy timelines pre-SB 684.

- Burke, Williams & Sorensen LLP – How Your Local Agency is Impacted by SB 684: “SB 684, signed into law Oct 11, 2023, requires ministerial approval (no hearing) for a housing project of 10 or fewer units meeting certain criteria… on a lot zoned multifamily ≤5 acres… added Gov Code Sections 65852.28, 65913.4.5, 66499.41 to make it faster and easier to build more homes on smaller lots.”

- San Gabriel Valley Habitat for Humanity – Advocacy Update: “Passed in 2023, SB 684 (Caballero) streamlines approvals for ‘starter’ homes in infill developments of 10 homes or less in multi-family zones. It also amends the Subdivision Map Act to make it faster and easier to split a single parcel into multiple, smaller properties, each with their own home.”

- CityStructure (Pasadena) – SB-684 Development in Pasadena: Local officials are required to decide on SB-684 projects within 60 days without public hearings; SB-684 allows lots ≤5 acres to be split into up to 10 lots (min 600 sf each), units <1,750 sf, with 4-foot side/rear setbacks and max 1 parking per unit (none if near transit), aligning with SB 9 standards.

- Governor Newsom’s Press Release (Oct 11, 2023): “SB 684 by Senator Anna Caballero (D-Merced) – streamlined approval processes: development projects of 10 or fewer residential units on urban lots under 5 acres.”